Poetic, Philosophical, Elegant:

Postmodern Pioneers in the Opera Opera Exhibition

There was no getting around Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose, first published in 1980. The story about the Franciscan scholar William of Baskerville and the novice Adson, who have to solve a series of bizarre murders in a medieval Benedictine abbey in Italy, also became a worldwide success due to the film adaptation with Sean Connery and Christian Slater and triggered a veritable medieval boom. What many fans didn't know: Umberto Eco was one of Italy’s most important postmodern thinkers long before his debut novel, internationally renowned as a cultural theorist and semiotician, concerned with the relationship between language and images. And his novel is a key literary work of postmodernism. It is about, as the allusion to Sherlock Holmes reveals, the play with signs, times, quotations. The book is full of layers of meaning, of literary, philosophical, and religious cross-references. The motif of the labyrinth, which features prominently in Eco’s work, is also characteristic of the narrative. Like a hall of mirrors, The Name of the Rose shows a fragmented reality and splintered, constructed identities that are constantly reassembled.

It is often forgotten how important Italy was for the advance of postmodern thought in the 1970s and 1980s, bringing it into mass culture playfully, poetically, and always with a certain elegance. And not only in literature, but especially in art, architecture, and design. Today, when the world seems more fragmented and enigmatic than ever, people are once again reflecting on this era—also in Opera. Opera. Allegro ma non troppo. We introduce you to four artistic pioneers of Italian postmodernism in the exhibition at Berlin’s PalaisPopulaire.

Architect, intellectual, and poet: Aldo Rossi

Interestingly, espresso machines and coffee pots helped bring postmodern avant-garde design into households around the world. For those who could not afford the motley, geometric, anti-functional furniture of the Milan-based Memphis Group, the design company Alessi offered cheaper options. While Frenchman Philippe Starck designed the legendary, useless, rocket-like Juicy Salif lemon squeezer for Alessi, Memphis founder Ettore Sottsass created pepper mills, cutlery, and wine coolers for the company. Another star Alessi designer was Italian architect Aldo Rossi (1931- 1997), whose espresso makers, kettles, and coffee pots became bestsellers. Ironic and imaginative, they offer architectural art in miniature, like Rossi’s real-life architectures inspired by the domes of Venetian churches, lighthouses, and water tanks on New York’s rooftops. ,As part of Opera Opera, Rossi’s model for the reconstruction of the Teatro Carlo Felice in Genoa is on view, which he realized in the early 1990s, with a completely modernized interior, but with a historic façade.

It is worth getting to know his other spectacular designs. Rossi distilled basic elements from historical cities, cubes, cones, columns, and gabled roofs, which he transformed into a reduced, typological, yet incredibly theatrical architecture. This earned him both cult reverence and blatant rejection, which left him artistically isolated even at the the end of his life. While his projects abroad were considered almost gigantomaniac, he built fewer and fewer of them in Europe. Hardly any of his students and companions followed him in the last part of his life. People found his red, green, and blue buildings from the late years too colorful, and many said they looked as if they were put together from building blocks: the Lighthouse Theatre with its lighthouse in Toronto, the office complex on Berlin’s Schützenstrasse, cloned together from different facades, Disney headquarters in Orlando, which looks as if a giant child put it down in a Californian wasteland.

Rossi was not only an architect, but also an intellectual and a poet. Starting in the 1970s, he implemented spectacular projects all over the world, and in 1990 he received the Pritzker Prize, the highest architectural award. But Rossi also has a reputation as a man who drove too fast, drank too much, and always lived in the fast lane. He left behind an architecture that, according to the art historian Kurt W. Forster, is slumbering like Sleeping Beauty, still waiting to awaken.

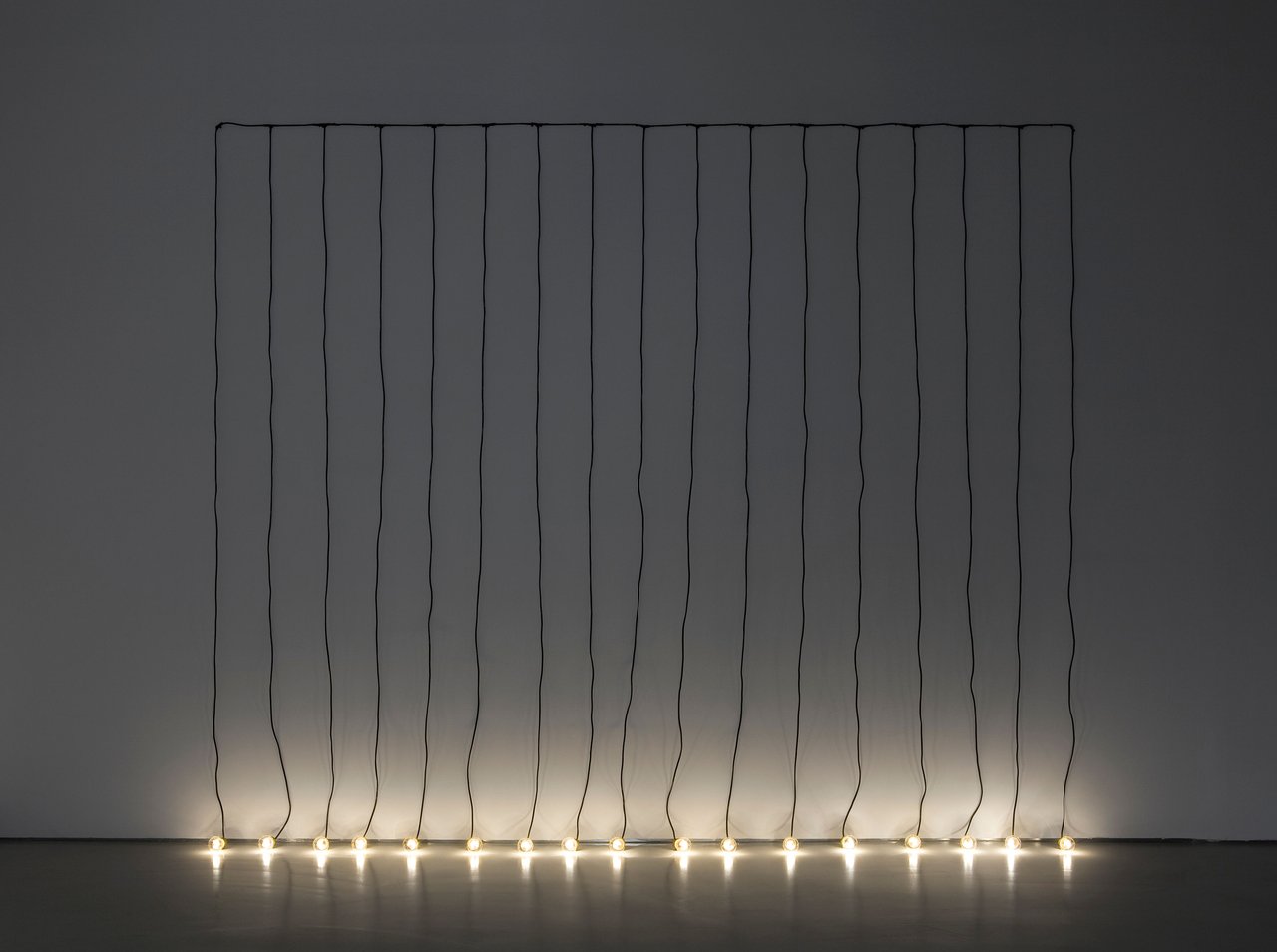

Mirror images, Arte Povera: Michelangelo Pistoletto

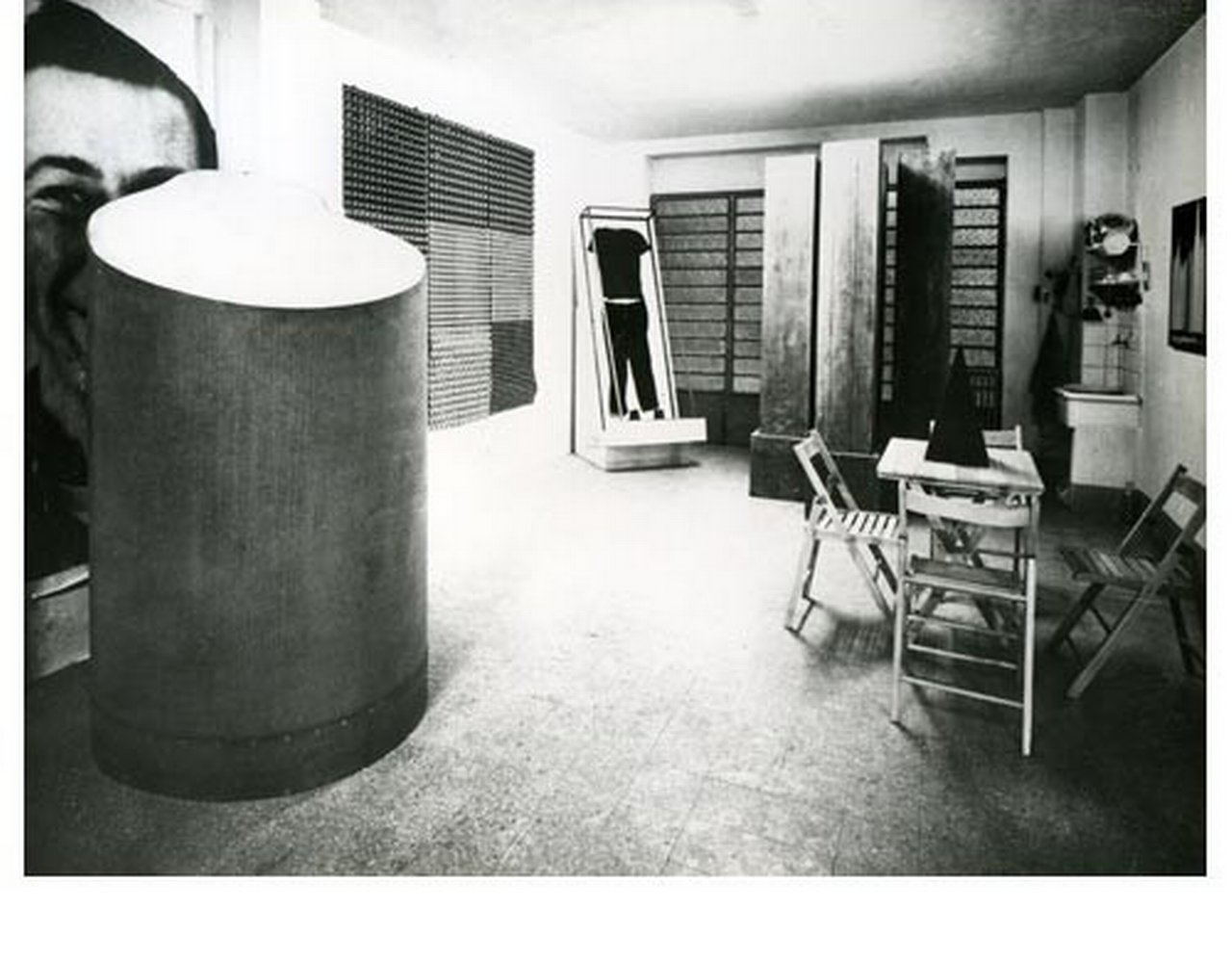

A Michelangelo for the twentieth century: Already at the age of 22, Pistoletto, born in 1933, showed his first exhibitions, before embarking on a world career in the early 1960s with his huge painted mirrors. These mixtures between objects and paintings are self-portraits for those who see themselves reflected in them. And, of course, in the smartphone age, entice people to photograph themselves in them. Yet even though Pistoletto says his mirror images have always been selfies, he was not concerned with narcissistic self-reflection, but rather—like Umberto Eco—sought to reflect on image and likeness, self and self-image, on transience, the construction and deconstruction of perception and reality. But no sooner had the often huge mirror images set in gold frames become something like Pistoletto’s trademark than he underwent a radical change between 1965 and 1967 with his series of “Minus Objects.” The minimalist light work Quadro di fili elettrici (1967) presented in Opera Opera, which consists of nothing more than a field of light bulbs wired together, was also created in this spirit. Pistoletto’s completely heterogeneous Minus Objects are hardly distinguishable from everyday objects; they are often “poor” scrap materials, found objects such as a cardboard rose or an industrial lamp into which a green light bulb was screwed.

The Minus Objects dispense with the conventions of art and marketability in a Dadaist and lyrical manner, eschewing a fixed artistic style. In keeping with Roland Barthes’ proclamation of the “death of the author” in 1968, they question artistic authorship. Critics reacted dismissively, the market value of Pistoletto’s earlier Mirror Paintings froze, and collaboration with many gallery owners broke off. Nonetheless, the series paved the way for the Arte Povera movement, postulated just a year later in 1968 by the curator Germano Celant. The group, which included artists such as Mario Merz and Jannis Kounellis alongside Pistoletto, countered the Italian economic miracle with a, poor, deliberately modest practice. This art can be seen as an anti-monumental counter-narrative to modernism’s functionalism and belief in progress, constructed from everyday materials and fragments. The fierce reactions it provoked at the time have faded. Pistoletto’s works have long since been sold at top prices. In 2003, he received the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale, and even at the age of almost ninety, he still participates in major international exhibitions.

Michelangelo Pistoletto

Image Courtesy Fondazione MAXXI,

© Michelangelo Pistoletto

Photo: Patrizia Tocci

Pistoletto-Minus Objects, 1965-1966 Pistoletto’s Studio,Torino 1966

Photo: P. Bressano

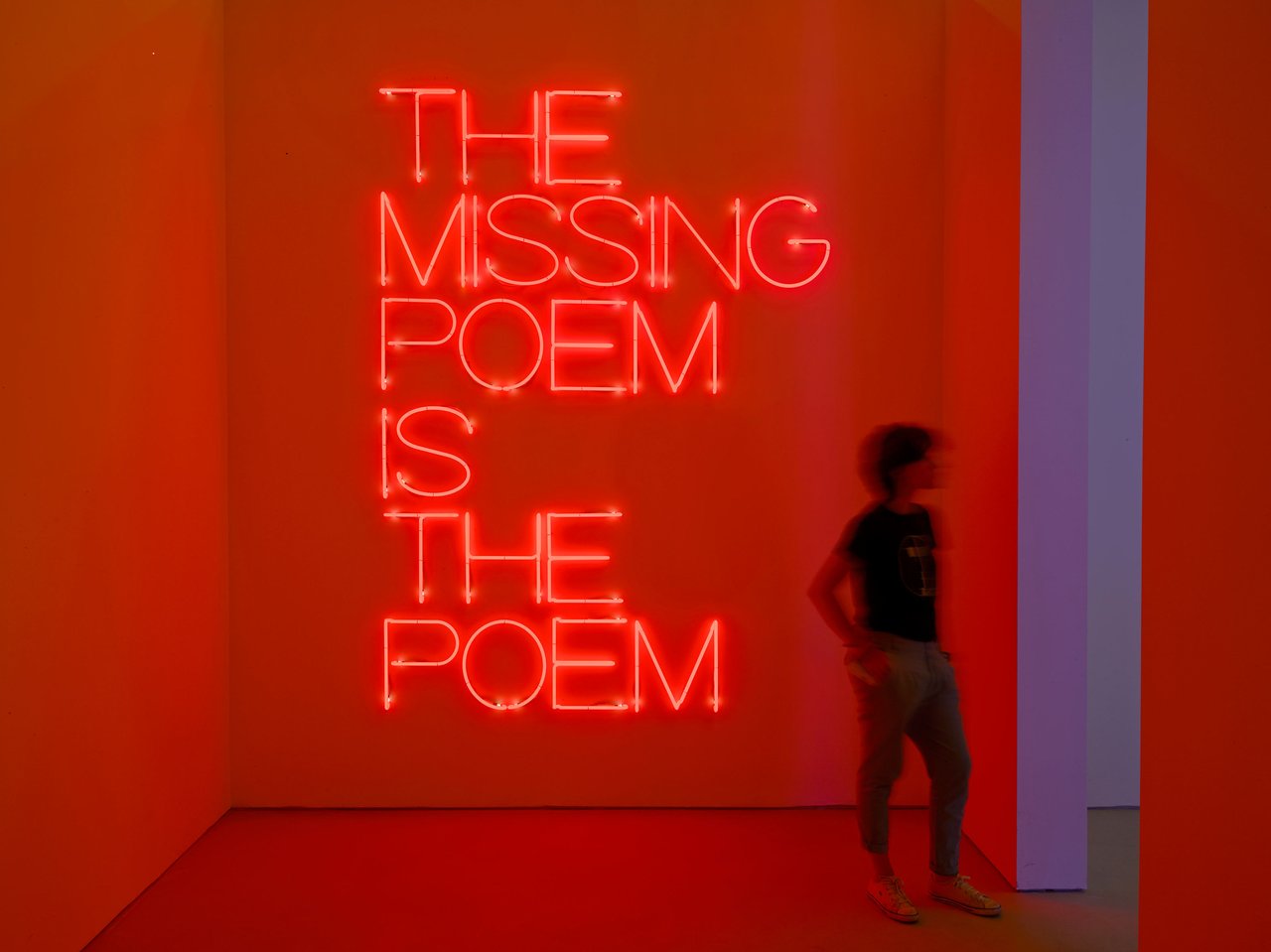

Neon poems: Mauricio Nannucci

“The missing poem is the poem”: this simple, seemingly paradoxical sentence, which Mauricio Nannucci illuminated in orange-red neon letters in 1969, can be viewed as mourning the loss of poetry in the modern world. But it could also simply be an experiment involving the serial stringing together of words, a kind of writing exercise. Born in 1939, Nannucci began to study semiotics, the relationships between language, writing, and images, in the 1960s. Like many conceptual artists of the time, he was inspired by linguistics and worked in various media, including photography, video, artist books, and sound installations. In 1967, he used blue tinted neon glass for a text for the first time—Alfabetofonetico. Between 1968 and 1969 he produced neon works such as Blue, Red, Corner, Colors, and the aforementioned The Missing Poem is the Poem, which Nannucci made in different shades of color, whereby the “radiance” of his linguistic constructions changed in the truest sense with each variation. From 1979 onward, he created large light installations; entire spaces of color, light, language, and writing; text that shines on the body; text spaces; and three-dimensional poetry. Nannucci became one of the world’s most important light and neon artists. Some visitors to Opera Opera may wonder why Nannucci’s style of neon looks so familiar. It is because of the many commissions he has realized, among others in the courtyard of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice.

Although the starting point of Nannucci’s works is conceptual, analytical, and reduced, and neon is actually considered a cold medium, they touch us in a strangely emotional way—like a “missing poem” that is found again.

Image Courtesy Fondazione MAXXI,

© Maurizio Nannucci

© Maurizio Nannucci

Mythical, deconstructed self: Luigi Ontani

In 1970s and 1980s European art he is one of the artistic nomads who, like Francesco Clemente, Sandro Chia, and the painters of the Italian Transavanguardia, was drawn to the East. He went to Afghanistan or India, seeking out symbols, myths, and spirituality, embarking on a journey to the depths of the self. And this, in Ontani’s case, is thoroughly postmodern, an ever-changing construct, fluid, in process. Ontani experimented with a wide variety of media. When he finally moved to Rome in 1970, he had already been experimenting for two years with his famous photographic tableaux vivants, in which he focused on himself, using his body to depict various mythological themes and motifs. “Le Ore” from 1975 is a work that, while remaining in the tradition of this photography, also has a performative dimension—each image is the result of a staging curated by the artist down to the smallest detail. Ontani transforms himself into Narcissus, Leda and the Swan, Dante, and Saint Sebastian, whose roles he reinterprets. The almost life-size photographic works are arranged like the hours of a clock, each image representing a time of day, showing different references to art history, from Antiquity to the Renaissance, Symbolism, and Romanticism. And of course there is postmodern irony, which in Ontani’s work is coupled with a sense of drama and a delight in exaggeration. Identity, for him, is a mystical, artistic, and at the same time “queer” construction, anticipating the gender debates of the 1990s. As with Rossi, Pistoletto, and Nannucci, today Ontani's work clearly shows the extent to which the pioneering achievements of these artists have helped shape current thinking.

Luigi Ontani

Photo: Mathias Schormann

© Luigi Ontani